Jane Addams, the first American woman to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, is one of the 20 inaugural honorees on the Rainbow Honor Walk in San Francisco’s Castro district. She is widely regarded as the founder of the social worker profession and one of the founders of the Peace Movement in the United States.

Early Years

Addams was born on September 6, 1860, the youngest of 20 children in a prosperous, politically-connected family in northern Illinois. Her father, John Addams, was a wealthy agricultural businessman who was also a bank president, a founder of the Illinois Republican Party, and a friend of Abraham Lincoln.

Jane had an early ambition of becoming a doctor so that she could help the poor. She received a certificate from Rockford Female Seminary in 1881, but longed to receive a proper degree from a university. That same summer, her father died of appendicitis, leaving each child with an inheritance equivalent today to $1.22 million each.

Addams moved to Philadelphia with other members of her family to Philadelphia to pursue a college education, but numerous factors – including a spinal operation, other health problems, and a nervous breakdown – conspired against her.

In August of 1883, Addams embarked on a two year tour of Europe. Upon her return, she decided that she could help the poor without becoming a doctor.

Hull House

In 1887, Addams became inspired with the idea of creating a “settlement house,” a home in a poor urban neighborhood where “volunteer middle-class ‘settlement workers’ would live, hoping to share knowledge and culture with, and alleviate the poverty of, their low-income neighbors” (Wikipedia).

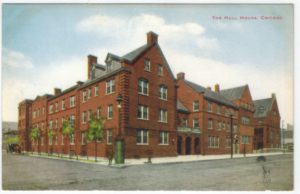

In 1887, she and her college friend, Ellen Gates Starr, co-founded a settlement house at Hull House, a rundown mansion in Chicago that had been built by Charles Hull in 1856. Addams initially paid for all of the house’s expenses, but she was soon able to reduce her outlay due to contributions from other wealthy women who became long-term donors.

The home would eventually become the residence of 25 women, and would be visited weekly by upwards of 2,000 people. Per Wikipedia:

The Hull House was a center for research, empirical analysis, study, and debate, as well as a pragmatic center for living in and establishing good relations with the neighborhood. Residents of Hull-house conducted investigations on housing, midwifery, fatigue, tuberculosis, typhoid, garbage collection, cocaine, and truancy. Its facilities included a night school for adults, clubs for older children, a public kitchen, an art gallery, a gym, a girls’ club, a bathhouse, a book bindery, a music school, a drama group and a theater, apartments,a library, meeting rooms for discussion, clubs, an employment bureau, and a lunchroom.[24] Her adult night school was a forerunner of the continuing education classes offered by many universities today. In addition to making available social services and cultural events for the largely immigrant population of the neighborhood, Hull House afforded an opportunity for young social workers to acquire training. Eventually, Hull House became a 13-building settlement complex, which included a playground and a summer camp (known as Bowen Country Club).

Lesbianism

Although same-sex relationships were kept very low-key in the late 1800s and early 1900s, she had what was at minimum a “romantic friendship” with Mary Rozet Smith, who moved into Hull House in 1890. They owned a summer home together in Maine. When they traveled together, they always shared a double bed. Whenever they were apart they would write to each other once or twice a day. It’s clear from their letters that they considered themselves to be a married couple.

Politics and the Peace Movement

In the late 1890s, Addams became deeply involved in the Peace Movement. She was a strong supporter of Theodore Roosevelt’s 1912 presidential campaign. She was elected national chairman of the Women’s Peace Party in 1915.

She was outspoken in her advocacy for the women’s suffrage movement, believing that women could extend their traditional caretaking role in the home into becoming caretakers of their communities through political action. Although she did not actively campaign for the ratification of the 18th Amendment, she supported Prohibition, believing that houses of prostitution, which she abhorred, could not survive without alcohol.

She became an early member of the American branch of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation, and was a member of the Fellowship Council until 1933. Her writings and speeches helped form the League of Nations and were later used as the basis for the United Nations.

Her advocacy for peace was recognized in 1931 when she became the first American woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Addams’ health issues precluded her from attending the ceremony (she died four years later on May 21, 1935), but she donated her winnings to the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

The San Francisco Connection

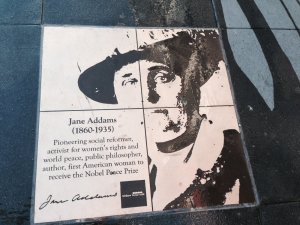

In 2014, Jane Addams was among the first 20 LGBT people recognized on the Rainbow Honor Walk in San Francisco’s Castro district. Her bronze plaque appears first on the west side of the 400 block of Castro Street, near 440 Castro.

The plaque’s inscription reads:

Pioneering social reformer, activist for women’s rights and world peace, public philosopher, author, first American woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize.