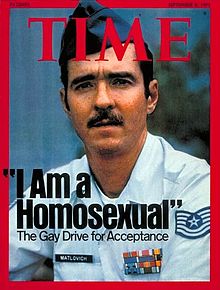

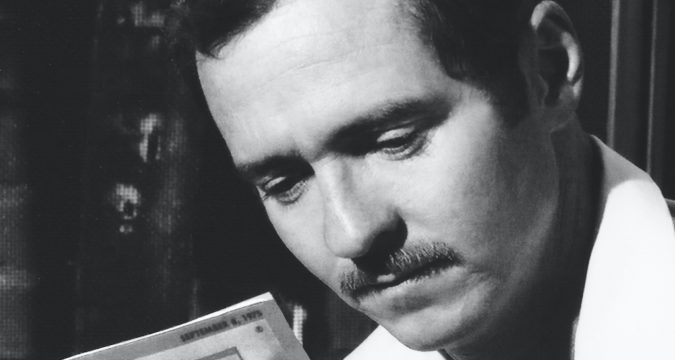

On September 8, 1975, Leonard Matlovich appeared on the cover of Time magazine with the headline, “I Am a Homosexual,” catapulting him into the national spotlight and making him perhaps the second best-known gay man of his time after Harvey Milk.

Matlovich was a Vietnam veteran, recipient of the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star, who in March of 1975 deliberately came out to his military leadership as a gay man to test the military’s anti-gay policies. Despite his exemplary service, he received a Less than Honorable discharge, which he fought … and won.

Early Life

Leonard Matlovich was born July 6, 1943, the son of a career Air Force sergeant who spent his early years bouncing through military bases throughout the South. His family later converted from Roman Catholicism to Mormonism.

He enlisted in the Air Force at the age of 19 shortly before the start of the Vietnam War and served three tours of duty there. He received a Purple Heart after being seriously wounded by stepping on a land mine.

Once he was stationed stateside in Florida, he began frequently gay bars in Pensacola and, at the age of 30, slept with a man for the first time. He began to quietly come out to friends, but remained closeted to his family and his colleagues.

Military Challenge

In 1974, after reading an interview with gay activist Frank Kameny, he contacted Kameny and the two began to strategize for how Matlovich, with his exemplary record, could help challenge the military’s anti-gay policies. He delivered a letter to his commanding officer on March 6, 1975, outing himself.

At the time, the military had an exceptions policy that allowed gays to remain in the military if they could argue extenuating circumstances, such as a drunken one-time act, known sarcastically as the “Queen for a Day” exception. But Matlovich refused to sign a pledge stating he would never again engage in a homosexual act, and he received a Less than Honorable discharge in October 1975.

Matlovich sued for reinstatement. When the military could not explain why he shouldn’t qualify for the “Queen for a Day” exception – which had subsequently been abolished but still applied to him because it was in effect at the time of his discharge – US District Court Judge Gerhard Gesell ordered his reinstatement and promotion in October of 1980. The Air Force countered with a financial settlement of $160,000 and, fearing that they would simply find some other pretext for discharging him, he accepted it.

Though the military continued to discharge gay service members, including during the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell regulations that began in 1993, the policy was changed to grant them an honorable discharge. In 2010, Congress repealed Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell pending certification from the military leadership that it would not harm military cohesion, and on September 20, 2011, DADT formally expired.

San Francisco

Matlovich moved to San Francisco in 1978 where he became one of the rarest of San Francisco gays: a Log Cabin Republican.

In 1981, he took his settlement from the Air Force and opened a pizzeria in the Russian River town of Guerneville. When AIDS struck the gay community in the early 1980s, Matlovich sold his pizza restaurant in 1984, touring Europe for a time before living briefly in Washington, D.C. in 1985 and then returning to San Francisco.

In the fall of 1986, Matlovich fell ill and was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS. This spurred him into a new phase of activism: advocacy for the care and treatment of people with AIDS.

Death

On May 7, 1988, Matlovich gave what would be his final public speech at the State Capitol in Sacramento during the March on Sacramento for Gay and Lesbian Rights.

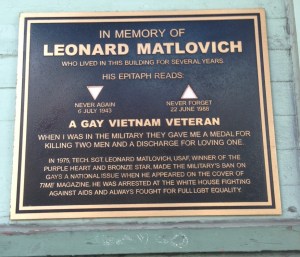

On June 22, 1988, little more than a month later, he died of AIDS-related complications in Los Angeles. He was buried at the Congressional Cemetery where his tombstone, instead of his name, reads, “When I was in the military, they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.”

A plaque in his memory is on the wall of the apartment building at the corner of 18th and Castro in San Francisco where he once lived. Another plaque in his memory has been installed on Halsted Street’s Legacy Walk in Chicago.